I’ve been away from the Eleanor Blog for some time as I had both a heavy human rights teaching load (Human Rights; Genocide) as well as organizing the Human Rights and the Humanities Week. Which also included a remarkable lecture by the Mideast Director of Human Rights Watch, Sarah Leah Whitson. The week was a great success and the study and teaching of human rights has really begun to blossom at UC Davis, like our redbud and ceanothus plants.

I am coming back to the blog, in part because of real sense of resignation over the turn of events in Syria and in particular the attacks on children. The depravity encompassed by the assault on Syria’s children is a shocking new low, even for the régime in Damascus. 384 have been killed – around 10% of the total casualties and thousands have been rounded up and tortured.

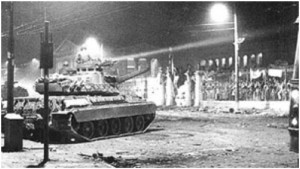

Broadly, it strikes me that this round has to go to House of Assad. The last two weeks’ attack on Hama and Idlib had the feel of “mopping up” operations and weren’t characterized by the slower escalation that took place in Homs. The Syrian régime senses that it can act with impunity and as long as it doesn’t escalate beyond light artillery and tanks, can pretty much do what it wants.

Even though the EC placed additional sanctions on the Syrian super-elite, including Asma, Bashar’s wife, the US has toned-down its rhetoric to delink humanitarian assistance from régime change. This is being done for Russia’s benefit and may lead to some form of real humanitarian help. On the other hand, this public change in rhetoric (the Annan Plan) has given the régime additional space to maneuver.

Human Rights Watch’s reporting on the rebel Free Syrian Army’s (FSA) war crimes, that of the Vatican on ethnic cleansing in Homs and other sources are undermining international support for the FSA and other Syrian rebel forces. Without a reliable non-Assad partner, régime change seems less attractive than “régime reform.” I think that what this also means is that the urban middle-class coalition supporting Assad will continue to do so even though the sanctions will begin to really hurt. For Arab Christians, Armenians and the urban middle-class elite this is an existential problem.

The recent meeting of the Friends of the Syrian People in Istanbul where aid was pledged to the rebels notwithstanding, I don’t see the régime being dislodged anytime soon and rather repression will continue and mount.

However, the international human rights community has begun to call attention to the fact that children are targeted for torture and abuse by the régime to an unprecedented degree. I think it’s worth exploring why the Syrian secret police has adopted this tactic.

First some facts: Human Rights Watch and the UN have both documented widespread detention, torture, and killing of Syrian children.

Human Rights Watch quotes one Hossam, age 13 who was held for three days in a military detention facility in Tel Kalkh:

Every so often they would open our cell door and yell at us and beat us. They said, “You pigs, you want freedom?” They interrogated me by myself. They asked, “Who is your god?” And I said, “Allah.” Then they electrocuted me on my stomach, with a prod. I fell unconscious. When they interrogated me the second time, they beat me and electrocuted me again. The third time they had some pliers, and they pulled out my toenail. They said, “Remember this saying, always keep it in mind: We take both kids and adults, and we kill them both.” I started to cry, and they returned me to the cell.

HRW tells us that Hossam and his family are now refugees in Lebanon.

But what these reports tell us is that the attacks on children are systematic. There is a rhyme and reason to this horror.

This has in large part to do with the role of children in Syrian and Middle Eastern society more generally, as well as the specific position of youth in the Arab uprisings.

We forget this in the West, but children are not just offspring you take care of for 18 years and then they’re out the door. They are your future, especially among the urban lower-middle class and rural people of Syria. They are an investment – a biological 401k. There is little or no safety net and your children will care for and comfort you in your old age.

Children are targeted because of their inherent value to adults. Protecting your children is also a point of honor; taking and torturing them undermines the very stability and integrity of the home.

Reports also indicate that children are being subjected to rape. This is calculated to demoralize and discipline the régime’s opponents, and to suppress the participation in demonstrations and activism by girls, in particular.

Young people – 13, 14, 15 year olds have been at the forefront of the revolutions in the Middle East. Youth has been the vanguard of these movements, in part because of their ability to master social media, and also they know that they have the most to gain from change. I think the Syrian régime also knows that it is involved in a generational struggle for control of the region.

Breaking young people now is a key element of that struggle for the future.