Turkey is a remarkable study in contrast and contradictions. As an impoverished grad student I once lived in Istanbul’s “infamous” neighborhood Sormagır Sokak, (the name of which is a slightly off-color pun in Turkish) which was home to conservative peasant immigrants from the Black Sea and transvestite singers who often headlined the high-end nightclubs off of Istiklal Caddesi nearby. Turkey has a long history of female impersonator singers, some of whom have reached great fame with vast numbers of fans among the country’s overwhelmingly conservative society.

In the mornings on the way to the archives, I’d watch the tired singers walk home after a night of working, their hair and makeup in stark contrast to the hints of a beard rising on their cheeks. The immigrants would sit on the front stoops of the apartments eating seeds and chatting. Relations between the two communities was usually live and let live, but tensions did exist that could lead to conflict.

Turkey was among the first states to decriminalize homosexuality. But the Turkish military views it as a mental illness and proving one’s homosexuality is a way to escape mandatory military service. Still, over the last two-decades a growing movement for Gay Rights has emerged in Turkey, especially as the country’s civil society becomes more integrated with Europe’s. Yet as that movement has grown and gay men, in particular, become more open in their practice, human rights activists and groups, including Amnesty International Turkey have noted the occurrence of gay “honor killing.”

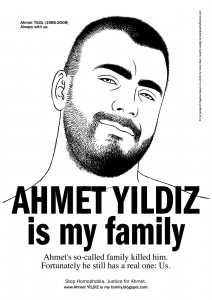

The case that continues to capture international attention is that of Ahmet Yıldız. Yıldız was a 26-year-old physics grad student who had represented Turkey at a Gay Rights gathering in San Francisco. Gay rights activists believe he was the first Turk to have been targeted for “honor killing” because of his sexuality. Leaving a café near the Bosphorous on a warm July evening in 2008 assailants attacked and shot and killed him.

The Turkish authorities finally issued an arrest warrant for his father, whom they believed killed his son, but only after the elder Yildiz had fled the country. Honor killing is a reality in Turkey, as it is elsewhere, where the victims are usually women who have “dishonored” the family because of some imagined or real illicit sexual act or having been raped. Despite increasing punishments for this kind of killing and the Turkish justice system’s abandonment of family honor as mitigation in sentencing, it continues. One horrifying consequence of the increasing legal sanction is that families will have one of their underaged children carry out the killing, knowing that they can only be imprisoned for a few years.

A remarkable and touching campaign in Yildiz’s memory is playing out on the walls of Istanbul’s Beyoglu neighborhood, where posters with his face and captioned by the phrase “Ahmet Yildiz is my family.” It’s accompanied by a website where people can join his “family.”

In the case of the Turkish Armenian intellectual Hrant Dink (2007) it was a teenager tasked with carrying out the honor killing. Dink was the most prominent Armenian intellectual in Turkey at the time of his murder. He was singled out for death in part because of his stand on the recognition of the Armenian Genocide and the broader sense that his behavior had insulted Turkish national honor. A famous picture of Dink’s murderer standing with smiling policemen after his arrest suggested that if not explicitly sanction by elements of the Turkish state, the killing was at least understood as a legitimate act of social discipline. Thus, it was ok to kill the Armenian because he insulted Turkey and he’s only a gavur, just as its ok to kill the gay guy because he violates society’s social norms and the rape victim because she dishonored the family and was asking for it.

Is the killing of women and gay men for reasons of family honor “cultural” where the murder of Dink was “political?” My sense is that there is a critical correlation between them. The tolerance of these acts by society and the elements of the state — granted Turkey has prosecuted in some cases, though often only following international pressure — creates a culture of social impunity, where non-state actors can violate the human rights of sexual and ethnic minorities and women and face lesser punishment, because of the perceived lesser humanity of the victims.

The case in Turkey points to how important it is to link the protection of the human rights of sexual minorities into broader protections and campaigns on behalf of other kinds of minorities and groups. It also raises other questions about the way appeals to culture and tradition can come into conflict with human rights norms and even how pressure on behalf of gays and minorities in a place like Turkey can be perceived as alien and itself a form of cultural oppression.

A possible path was proposed this last week by British PM David Cameron who has pledged to cut foreign aid to those countries criminalizing homosexuality. The problem there is that this kind of outside pressure often works at cross-purposes in the local context, making life MORE difficult for local human rights activists. The most effective and long-range solution lies with supporting civil society in a places like Turkey and remembering that we too in the West are in Ahmet’s and Hrant’s families.

Salon.com has longer article on this topic

also read Human Rights Watch’s remarkable report on the situation in Turkey.